Ali Reza‛Abbāsī (Tabrīzī), a renowned Iranian calligrapher and inscription artist of the 10th/15th and 11th/16th centuries. Little is known about ‛Alī Reza’s birth and early life. He was likely born in the mid-10th/15th century in Tabriz. He learned the six canonical scripts of Islamic calligraphy and the art of inscription* writing from ‛Alā’ al-Dīn Muhammad Tabrīzī, who himself was a student of his uncle, Ali Beyk Tabrīzī (d. 1551/958), a distinguished inscription artist. However, Ali Reza is not mentioned in Rawḍāt al-Jenān wa Jannāt al-Janān, a biographical work covering the lives of ‛Alā’ al-Dīn Muhammad, Ali Beyk Tabrīzī, and the circle of calligraphers of Tabriz.1 Similarly, in the treatise Kashf al-Hurūf, which frequently references the Tabriz school of calligraphy and calligraphers such as ‛Alā’ al-Dīn Muhammad and ‛Abd al-Bāqī Tabrīzī, there is no mention of Ali Reza.2 It has been said that Ali Reza learned the Nasta‛līq script from Muhammad Ḥusayn Tabrīzī. However, his name does not appear among the students of this calligrapher in the treatise Manāqeb-e Hunarvarān.3 This omission suggests that at the time, Ali Reza was at the beginning of his career and had not yet gained recognition among the calligraphers of Tabriz.

In 993/1585, following the Ottoman conquest of Tabriz, Ali Reza migrated to Qazvin, the first Safavid capital, he engaged in inscription writing, Quran transcription, and the creation of calligraphic panels in the Jāmi‛ Mosque of Qazvin. The turning point in Ali Reza’s life was his association with the court of Farhād Khān Qarāmānlū, a military commander under Shāh ‛Abbās I, who took him along for two years to Khurasan and Mazandaran.4 In Shawwāl 1001/July 1593, Ali Reza entered the ranks of Shāh ‛Abbās’s personal entourage at the monarch’s request and settled in Isfahan, the newly established Safavid* capital.5 From that point onward, he signed his works as “Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī” instead of “Ali Reza Tabrīzī.”

Shāh ‛Abbās’s admiration and trust in Ali Reza led to his appointment in 1598 /1006 as the head of the Royal Library, succeeding Ṣādiq Beyk Afshār (d. 1610/1018/), the renowned painter. It seems that Ṣādiq Beyk’s dissatisfaction with his dismissal later fueled tensions between the two artists. In Dhū al-Qa‛da/January of the same year, Ṣādiq Beyk complained to Shāh ‛Abbās* about Ali Reza’s negligence in completing the Muraqqa‛-e Kherqa, an album featuring works of calligraphers and painters. In response, the Shah urged the completion of the project.6. With Shāh ‛Abbās’s support, Ali Reza amassed considerable wealth and property in Isfahan. It is said that in 1611/1020, Shāh ‛Abbās purchased Ali Reza’s estates south of Naqsh-e Jahān* Square for 300 tūmāns to facilitate the expansion of the square and the construction of the Masjid-e Jāmi‛-e* ‛Abbāsī. That same year, the Shah acquired Ali Reza’s Bāgh-e Jannat (Garden of Paradise) to establish the Tabrīzīyān neighborhood.7

The relationship between Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī and the murder of Mīr ‛Emād Qazvīnī is a contentious topic in the history of calligraphy. Given the contradictory nature of Shāh ‛Abbās, whose character ranged from kindness and simplicity to decisiveness and bloodshed, survival at court depended on absolute loyalty to the Shah’s will.8 Court sources, such as ʿĀlam-Ārāy by Eskandar Beyg Munshī Turkamān, could not openly discuss Shāh ‛Abbās’s involvement in Mīr-‛Emād’s death. It has been suggested that the accusations of Sunnism against Mīr ‛Emād, combined with his outspoken and bold manner in opposing the Shāh, were factors that led to his murder.9 However, given that Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī is described as a man of impeccable character and pure nature,10 his involvement in Mīr‛Emād’s death seems unlikely. Since no works by Ali Reza have been identified after 1038, it is reasonable to assume that his life ended around the same time as that of his patron, Shāh ‛Abbās.

Ali Reza’s Style in Thuluth Inscription

During the 10th/16th and 11th/17th centuries, a large number of calligraphers specializing in inscriptions were in competition with one another. ‛Abd al-Bāqī Tabrīzī, a contemporary of Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī and a fellow student of ‛Alā’ al-Dīn Muhammad Tabrīzī, wrote the Thuluth script with exceptional skill, to the point where his mastery was even considered superior to that of Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī.11 Muhammad Ṣāleḥ Mawlavī and Muhammad Bāqer Bannā were also skilled inscription calligraphers. Ṣaḥīfī Jawharī Shīrāzī was another prolific inscription artist during the time of Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī. Lesser-known calligraphers, such as Ghiyāth al-Dīn ‛Alī Jawharī Shīrāzī, the inscription artist at the Imāmzādeh Hefdah-Tan shrine in Golpayegan, dated 1621/1031/, also belong to this group.12

The style of Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī in crafting individual words of Thuluth calligraphy reflects a strong influence from the techniques of ‛Alā’ al-Dīn Tabrīzī. In terms of composition and layout, however, his early inscriptions—such as the one on the entrance of the ‛Ālīqāpū Palace in Qazvin—demonstrate a noticeable inspiration from the Timurid style. This influence is evident in his emphasis on the visual weight of the lower section (known as kursī dheyl) and the lightness and openness of the upper section (referred to as kursī ṣadr). Over time, Ali Reza developed a distinctive style of his own, marked by the precise alignment and sequencing of letters in both the upper and lower sections. His approach also featured a meticulously balanced interplay of density and openness, resulting in harmonious compositions throughout the entire inscription (Figures 1 and 2).

However, Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī used both Nasta‛līq and Thuluth scripts in his inscription signatures. Of these, fourteen signatures are in Thuluth, while four are in Nasta‛līq. The diversity in his signature styles is a distinctive feature of ‛Abbāsī’s calligraphic works.

Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī’s Nasta‛līq Inscriptions

In comparison to his Thuluth inscriptions, fewer examples of Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī’s Nasta‛līq calligraphy have survived. Some of his Nasta‛līq signatures, which are placed at the end of his Thuluth inscriptions, can be found around the cylindrical base of the dome at the Holy Shrine of Imam Reza, on the gilded plaques of the former shrine of Imam Reza (peace be upon him), and in the inscriptions at the Ganjalī Khān Caravanserai in Kerman. These examples reflect Ali Reza’s strong interest in Nasta‛līq script. Additionally, the influence of Mīr ‛Alī Heravī, the renowned 16th/10th-century Nasta‛līq master, is clearly evident in these works.

Table of Ali Reza‛Abbāsī’s Inscriptions Based on Location, Date, Script Type, Material, and Content of the Inscription.

| No | Location of the Inscription | Date | Script Type | Material | Content of the Inscription |

| 1 | Entrance of the ʽĀlīqāpū Palace in Qazvin | between the years 1001 and 1007/1592-1598 | – | Mosaic Tile | Commemoration of the patron of the building: Shāh ‛Abbās I of the Safavid Dynasty |

| 2 | Ganj‛alī Khān Caravanserai Entrance, Kerman |

1007/1598 |

Thuluth script with Nasta‘liq-style signature |

Tile |

Commemoration of Ganj‛alī Khān, the patron of the caravanserai, and praise for Shāh ‛Abbās |

| 3 | Maqsūd Beyg

Mosque |

1011/1602 | Thuluth | Mosaic Tile | Commemoration of the patron of the building, and praise for Shāh ‛Abbās |

| 4 | Portal of the Sheikh Lutfullāh Mosque | 1012/1603 | Thuluth | Mosaic Tile | Commemoration of the mosque’s construction commissioned by Shah Abbās.

|

| 5 | Around the cylindrical base of the dome at the Holy Shrine of Imam Reza.

|

1016/1607 | Thuluth script with Nasta‘liq-style signature | Gold | Account of Shāh ‛Abbās’s foot journey from Isfahan to Mashhad for pilgrimage and the restoration and expansion of the shrine of Imam Reza.

|

| 6 | Portal of Masjed-e Jāme‛ ‛Abbāsī in Isfahan | 1020/1611 | Thuluth | Mosaic Tile | Commemoration of the mosque’s construction commissioned by Shāh ‛Abbās.

|

| 7 | The tomb of Sheikh Amīn al-Dīn Jebrā’īl in Khalkhurān, Ardabil.

|

1021/1612 | Thuluth | Plaster | The wise sayings of Imam Ali in Nahj al-Balāgha |

| 8 | Rubāt Khargūshī Caravanserai, ‛Aqdā City, near Yazd |

1023/1614 |

Thuluth |

Stone |

Shāh Abbās’s command for the construction of the building and requesting God’s mercy for Shāh Ṭahmāsp |

| 9 | Under the Dome of the Holy Shrine of Imam Reza | 1024/1615 | Thuluth | Plaster (Mirrored) | Opening verses of Surah Al-Jumu’ah |

| 10 | Around the Dome of the Shrine of Khwājah Rabīʽ | 1024/1615 | Thuluth | Mosaic Tile | Reference to Shāh Abbās’s order for the construction of the building and a Ḥadīth of the Prophet mentioning the qualities of the believers and the friends of Allah. |

| 11 | Under the Dome of the Sheikh Lutfullāh Mosque | 1025/1616 | Thuluth | Mosaic Tile | Upper inscription: A Ḥadīth from the Prophet Muhammad regarding the etiquette of entering the mosque. Lower inscription: The complete verses of Surah al-Jumu‘ah and Surah al-Naṣr, along with phrases praising God and extolling the Prophet Muhammad. |

| 12 | Inside the shrine of Khwājah Rabīʽ | 1026/1617 | Thuluth | Plaster | A Ḥadīth from Jābir Anṣārī explaining the verse of Ule al-Amr as conveyed by the Prophet Muhammad. |

| 13 | The main entrance of Sheikh Ṭūsī Portico (Western Iwan Arch) in the Shrine of Imam Reza. | Between the years 1024 and 1026 /1615–1617 | Thuluth | Mosaic Tile | A Ḥadīth from Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī regarding the Five Holy People of the Ahl al-Bayt and the occasion of the revelation of verse 33 from Surah Al-Aḥzāb, a Ḥadīth from the Prophet Muhammad about the exalted status of Lady Fāṭimah, and following this, another Ḥadīth from the Prophet Muhammad narrated by Jāber ibn Abdullāh al-Anṣārī, explaining verse 59 of Surah Al-Nisā (the verse of Ulel Amr)

|

| 14 | The small iwans on both sides of the main entrance of Sheikh Ṭūsī Portico in the Shrine of Imam Reza. | Between the years 1024 and 1026 /1615–1617 | Thuluth | Mosaic Tile | Verses 58 of Surah Al-Baqarah and 73 of Surah Al-Zumar |

| 15 | The Qadamgāh (Imam’s Footprint) of Nishapur | Between the years 1024 and 1026 /1615–1617 | Thuluth | Plaster | The first eleven verses of Sūrat al-Jumuʿah |

| 16 | The Portal of the Cistern Iwan in the Sheikh Aḥmad-e Jāmī Complex

|

—— | Nasta‛līq | Plaster | Praising the patron and mentioning Imam Ḥusayn while drinking water |

| 17 | The Gilded Plaques of the Former Shrine of Imam Reza | —— | Thuluth | Gold | Āyat al-Kursī |

| 18 | The Gilded Plaques of the Former Shrine of Imam Reza | —— | Nasta‛līq | Gold | Poems in Praise of Imam Reza |

| 19 | Above the Portal of Sheikh Lutfullāh Mosque

|

1028/ 1619 | Nasta‛līq | Mosaic Tile | The phrase ‘māye-ye muḥtashamī khedmat-e awlād ‘Alī’’ [A little wealth of muḥtashamī is dedicated to Ali’s children] and possibly the signature inscription ‘Muhammad Rezason of Master Ḥusayn Bannā Esfahānī |

| 20 | The Tomb of Shāh Esmāīl in the Shrine of Sheikh Ṣafī al-Dīn Ardabīlī

|

1037/ 1628

|

Thuluth |

Plaster |

Sayings of Imam Ali regarding the providence of God and advice to the people.

|

Transcription of the Quran

According to Gulestān-e-Hunar, Ali Rezawas engaged in transcribing a Quran manuscript at the Jāme‛ Mosque in Qazvin.13 While no examples of his handwritten Qurans from Qazvin have survived, a beautifully crafted manuscript of the Quran, now housed in the library of Āstān-e Quds Raḍavī, is attributed to him. It is highly likely that Ali Reza transcribed this manuscript between 1601–1603/1010 – 1012, during his time in Mashhad, on commission from Shāh ‛Abbās.14 The mention of Shāh ‛Abbās’s name and the exquisite quality of the manuscript make it even more probable that it was transcribed by Ali Reza.

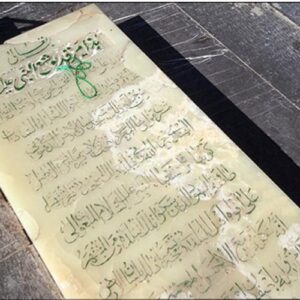

The overall transcription style of this Quran employs gilded muḥarrer script alongside black ink. The lines alternate between gold and black, creating a pleasing contrast of colors. All gilded and bold (jalī) line are outlined with extremely fine, hairline strokes. Some lines of the Quran follow a straightforward linear style, while others are inspired by epigraphic compositions, particularly those with an inscription-like arrangement. The epigraphic style in this Quran is characterized by high density and compactness, with creative variations in the placement of letters and words. In certain lines, this is achieved using the full width of the pen, a technique known as bold script (jalī writing). This reflects the scribe’s particular interest in the tradition of epigraphic calligraphy, where the arrangement and interlocking of letters hold significant visual value. It appears that Ali Reza, in transcribing this Quran, was influenced by the grand, inscription-like Quranic styles of the 8th to 10th hijra centuries (14th to 16th centuries), particularly the Quranic manuscripts from the Timurid period. This connection is plausible given Ali Reza’s position as the head of the Royal Library, which would have granted him access to manuscripts from that era.15 (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Verses from the Quran, Signed by Ali Reza‛Abbāsī

A piece written in the Naskh script by Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī, in the style of ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Tabrīzī, containing the sayings of religious and philosophical figures, remains in the personal collection of ʿAlī Khushnevīs-Zādah Esfahānī (Figure 4).

Ali Reza’s Nasta‛līq Style

- Panel Writing and Chalīpā

There are not many dated works by Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī in the Nasta‛līq script. Although the Gulestān-e Hunar mentions Ali Reza’s engagement in “writing and panel composition,”16 it seems that, at the Safavid court of Shāh ‛Abbās, he practiced panel writing and manuscript transcription less frequently than other calligraphers of his time. A unique work bearing the signature Ali Reza Tabrīzī, containing a poem in Turkish (preserved in the Karīmzādeh Tabrīzī collection; Figure 5), is among Ali Reza’s creations prior to his association with the Safavid court and reflects the influence of Muhammad Ḥusayn Tabrīzī’s style.

Ali Reza closely followed the Nasta‛līq style of Mīr Ali Heravī, while skillfully integrating elements of monumental inscription design into the overall composition of his works. His Nasta‛līq script is distinguished by the use of a larger pen size compared to the handwriting of Mīr ‛Emād, reflecting the influence of his experience in monumental inscriptions. A review of Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī’s body of work, especially his Chalīpās, reveals that he not only refined and elevated the style of Mīr Ali Heravī but also brought it to a new level of prominence and sophistication. He seems to serve as a transitional figure, bridging the perfected style of Mīr Ali Heravī and the distinctive approach of Mīr ‛Imād (Figure 6). Additionally, a rare Sīyāh-Mashq signed by Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī is housed in the library of Istanbul University.17

- Albums and Manuscripts

A six-page album containing verses from Jāmī, dated 1598 /1007 (Art and History Trust Collection; Figure 7).18

A four-page prayer book (munājāt-nāme) of Khwāja ‘Abdullāh Anṣārī, dated 1600/1008, commissioned by Mīr ‘Abd al-Qādir Maṣūmī in Mashhad (Āstān-e Quds Razavī Library).

A manuscript of the history of Bāyazīd Khāndigār of Rum (Asian Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg), consisting of 145 pages with nine lines per page, dated 1601/1010/.19

A manuscript of the Mathnavī Makhzan al-Asrār by Ḥeydar Khwārazmī, dated 1618/ 1027 (Topkapı Palace Library), which had previously been left incomplete in 1614 /1023 with the collaboration of Reza ‘Abbāsī the painter and Mīr ‘Imād.20

Students of Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī

Due to his extensive involvement in monumental inscription work, his role as the head of the royal library, and the comfort provided by royal patronage, Ali Reza likely had little motivation or opportunity to train a large number of students. As a result, unlike Mīr ‛Emād, he did not cultivate a wide circle of disciples and followers. Among his known students were his sons, Badī‛ al-Zamān and Muhammad Reza , also known as Mīrzā Khān Beyg. Badī‛ al-Zamān, who wrote poetry under the pen name “Badī‛ā” and was a skilled Nasta‛līq calligrapher, enjoyed the respect of Shāh ‛Abbās, much like his father, and lived at least until the reign of Shāh Ṣafī.21 Muhammad Reza , who excelled in the style of Thuluth and Naskh scripts, transcribed the manuscript Rijāl Kabīr (housed in the Tehran University Library) in the style of hidden (khafī) Naskh, with chapter headings written in the Riqā‘ script.22 Ne‛matullāh Mashhadī studied Nasta‛līq under Ali Reza during the latter’s time in Qazvin. Another follower, Mawlānā Faghān al-Dīn Bulbul, was skilled in Thuluth, Naskh, and Riqā‘ scripts.23 Aqā Ḥusayn Lavasānī, a calligrapher and poet of the 11th/17th century, is also mentioned as having been held in high regard by Shāh ʿAbbās. In one piece, Ali Reza honored him with the title “Master of Various Arts” (dhū al-funūn).24 In the field of monumental inscription writing, Ali Reza’s influence extended to his son Muhammad Reza Emāmī and his descendants, Muhammad Muḥsen and Ali Naqī. Other notable figures influenced by him include ‛Abd al-Raḥīm Jazā’irī, an inscription writer active in the late Ṣafavid period, along with countless other calligraphers who studied and practiced by closely imitating Ali Reza’s masterful inscriptions for generations.25 (Figure 8)

Forgery of Works Attributed to Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī

The fame of Ali Reza ‛Abbāsī, coupled with the existence of other calligraphers named Ali Reza, has led to ambiguities in attributing certain works to this renowned scribe. Works attributed to an Ali Reza active in Bukhara date from1524–1582/ 930 – 990.26 he shared name among these calligraphers has also contributed to the proliferation of forged works. For instance, the transcription of the Qaṣīdat al-Burda housed in the National Museum of the Quran, the Sūrat Yāsīn in Berlin State Library (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin) and an album (murraqaʿ) numbered 7450 in the University of Tehran Library have been attributed to Ali Reza ʿAbbāsī. However, the quality of the script in these works is noticeably inferior when compared to the authentic handwriting of Ali Reza ʿAbbāsī. 27(Figure 9)

/Shahāb Shahīdānī/

Bibliography

Esfahānī, Muḥammad-Ṣāleḥ, Tadhkerat al-Khaṭṭāṭīn, edited by Pejmān Fīrūzbakhsh, Nāmeh-ye Bahārestān, Vol. 6-7, Issues 11-12 (1384-1385/2006-2007).

Awḥadī Belyānī, Taqī al-Dīn Muhammad ibn Muhammad, Tadhkere-ye ‘Arafāt al-‘Āsheqīn wa ‘Araṣāt al-‘Ārefīn, edited by Sayyid Muḥsen Nājī Nasrābādī, Tehran: Asāṭīr, 1388/2009.

Bayānī, Mahdī, Aḥwāl wa Āthār Khushnevisān, Tehran, 1363/1984.

Shāhkārhā-ye Hunarī Āstāb-e Quds-e Raḍavī: Selected Nastaʿlīq Pieces, Mashhad: Astan Quds Razavi, 1391/2012.

Shukrullāhī, Eḥsānullāh, “Taṣḥīḥ Risāle-ye Kashf al-Ḥurūf by ʿEnāyatullāh Shushtarī,” in Majmūʿah-ye Maqālāt-ye Khaṭṭāṭī-ye Maktab-e Shirāz, Tehran: Farhangestān-e Hunar, 1390/2011.

Shahīdānī, Shahāb, Tāḥavvulāt-e Khaṭṭāṭī-ye ʿAṣr-e Ṣafavī bā Taʾkīd bar Āthār va Aḥwāl-e Ali Reza ʿAbbāsī, Isfahan: University of Isfahan, 1398/2019.

ʿĀlīafandī, Muṣṭafā, Manāqib-ye Ḥunarvarān, translated by Tawfīq Subḥānī, Tehran: Soroush, 1369/1990.

Falsafī, Naṣrullāh, Zendegī-ye Shāh ʿAbbās-e I, Tehran: University of Tehran, 1347/1968.

Qelīchkhānī, Ḥamīdredā, Ali Reza ʿAbbāsī, Tehran: Peykareh, 1395/2016.

Karbalā’ī Tabrīzī, Ḥāfeḍ Ḥusayn, Rawḍāt al-Jenān wa Jannāt al-Janān, edited by Jaʿfar Sulṭān al-Qarāʾī, Tehran: Būngāh-e Tarjumah wa Nashr-e Ketāb, 1344/1965.

Munajjem Yazdī, Jalāl al-Dīn Muhammad, Tārīkh-eʿAbbāsī yā Rūznāme-ye Mullā Jalāl, edited by Ṣeyfullāh Vaḥīdīnyā, Tehran: Vaḥīd, 1987.

Munshī Qumī, Aḥmad ibn Ḥusayn, Gulestān-e Ḥunar, edited by Aḥmad Suheylī Khwānsārī, Tehran: Bunyād-e Farhang-e Irān, 1987.

Naṣrābādī, Muhammad Ṭāhir, Tadhkire-ye Naṣrābādī, edited by Vaḥīd Dastgerdī, Tehran: Armaghān, 1938.

Harātī, Muhammad Maḥdī, Hunarpazhūhī dar Barguzīde-ye Qurʾān-e Karīm be Khaṭṭ va Kitābat-e Ali Reza ʿAbbāsī, Tehran: Farhangestān-e Hunar, 2006.

Soudavar, Abulʽalā, Art of the Persian Courts, New York: Rizzoli, 1992.

- Munshī Qumī, p. 40; Karbalāʾī Tabrīzī, vol. 1, pp. 370–371.[↩]

- Shukrullāhī, pp. 159–167.[↩]

- ʿĀlīafandī, p. 87.[↩]

- Munshī Qumī, pp. 40, 125.[↩]

- Munajjem Yazdī, p. 119; Munshī Qumī, p. 125.[↩]

- Awḥadī Belyānī, vol. 4, pp. 2123–2124; Munajjem Yazdī, p. 170[↩]

- Munajjem Yazdī, pp. 411–413.[↩]

- Falsafī, vol. 2, p. 77.[↩]

- Eṣfahānī, p. 19.[↩]

- Naṣrābādī, p. 207.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Shahīdānī, pp. 134–136.[↩]

- Munshī Qumī, p. 40.[↩]

- Harātī, pp. 20, 193.[↩]

- Shahīdānī, 1398: pp. 222–226.[↩]

- Munshī Qumī, p. 125.[↩]

- Qelīchkhānī, p. 24.[↩]

- Sūdāvar, pp. 286–287.[↩]

- Qelīchkhānī, p. 35.[↩]

- Sūdāvar, p. 273.[↩]

- Bayānī, vol. 1–2, pp. 97–98.[↩]

- Eṣfahānī, p. 22; Bayānī, vol. 3–4, p. 1169.[↩]

- Munshī Qumī, pp. 40, 41, 127.[↩]

- Bayānī, vol. 1–2, p. 167.[↩]

- Shahīdānī, pp. 237–241.[↩]

- Shāhkārhā-ye Hunarī dar Āstān-e Quds-e Raḍawī, p. 134.[↩]

- Shahīdānī, pp. 248–250.[↩]