Chehel Sutūn, a ceremonial palace from the Safavid* period in Isfahan, featuring twenty columns.1

The reason it is called “Chehel Sutūn” (Forty Columns) is the large number of its columns, then ‘forty’ here serving as a metaphor for abundance. It is also said that because the twenty columns of the palace are reflected in the pool in front of it,2 their total number is thus counted as forty. The Chehel Sutūn Palace is situated within a garden of the same name, covering an area of 67,000 square meters, located between Naqsh-e Jahān Square and Chahār Bāgh* Avenue.3

The original structure of the palace was reportedly built by the order of Shah ‛Abbās I (r. 1588–1629/996–1038), and assumed its present form during the reign of Shah ‛Abbās II (r. 1642–1666/1052–1077).4 An inscription* dated 1647/1057 attests to works carried out under Shah ‛Abbās II. Another inscription bears the date 1706/1118, indicating the year the building was restored following a fire during the reign of Shah Sulṭān Hussein*.5 The Eighteen-Column Hall and the Hall of Mirrors, along with the mirror-work and paintings of these halls (with the exception of the depiction of Nāder Shah*), all date from the time of Shah ‛Abbās II.6 The Safavid monarchy held certain festivities and formal audiences (salām ceremonies,) in this palace.7 During the Afghan invasions, parts of the palace’s ornamentation, including its splendid royal throne, were destroyed,8 though later Maḥmūd Afghan* took an interest in the building and sat upon its throne. By order of Shah Ṭahmāsp II*, the palace’s damages were repaired.9 In 1882/1300, when Mas‛ūd Mīrzā Ẓell al-Sulṭān was the governor of Isfahan, most of the palace’s precious furnishings were either lost or transferred to be used in his palace in Tehran (the Mas‛ūdīye building). Some of these items were also transferred to various museums around the world.10 During the governorship of Ẓell al-Sulṭān, the building first served as a workshop for sewing travel tents and later became a venue for receiving guests and housing the Provincial Council. Ẓell al-Sulṭān also held audiences there to hear the complaints of the populace.11 Chehel Sutūn Palace was inscribed on the List of National Monuments of Iran in 1931/1310.12 Since 1932/1311, the building has undergone multiple restorations.13 In 1948/1327, it was converted into a museum, and it now houses valuable collections.14

Chehel Sutūn Palace, covering an area of 2120 square meters, is built of brick and chiseled stone in a rectangular plan atop a stone platform approximately one meter high.15 On the eastern side of the structure stands the main portico, featuring eighteen sixteen- and eight-sided columns made from the trunks of plane and pine trees. The ceiling of this portico is adorned with beautiful paintings, part of which was damaged by rainfall in 1954/1333. At the center of the portico lies a marble pool, and behind it stands a hall known as the Hall of Mirrors, with a mirrored entrance and ceiling, flanked by two additional columns. To the north and south of the Hall of Mirrors, two large rooms have been constructed.16 Behind the Hall of Mirrors stands the Throne Hall, its ceiling covered by three domes. The Throne Hall is surrounded by three porticos on the north, south, and west sides. The western portico is the royal sitting area (shah-neshīn).17 The ceilings of the building are largely constructed with pine wood.18 The roof of the structure is pitched and double-layered, with its height varying from about 50 centimeters to over 2 meters in different sections.19

Around this structure, a water channel was constructed, along which stone fountains were installed. The rectangular pool in front of the palace is connected to it by this same water channel.20 This large pool, measuring 16 by 110 meters, lies to the east of the building and reflects the image of the palace.21 To the west of the building, symmetrically, another pool once existed between the palace and Chahār Bāgh Avenue, which was revealed during an archaeological excavation in 2005/1384.22 In addition to these two pools, there were also other pools to the north and south, as well as smaller basins scattered throughout the palace garden.23

The most important ornamentation of the palace consists of the gilding and murals of the Throne Hall and the two rooms adjacent to the Hall of Mirrors.24 The paintings of Chehel Sutūn, remarkable for their unparalleled variety in both quantity and stylistic approaches, depict diverse subjects such as Iranian monarchs hosting rulers from other lands, battles, hunting scenes, courtly feasts and celebrations, as well as literary artistic themes like the gatherings of Yūsuf and Zuleykhā and of Khusru and Shīrīn.25 A number of the palace’s wall paintings were influenced by the style of Reza ‛Abbāsī*.26

The walls of the palace are clad halfway up with white marble, while the upper portions are adorned with paintings, mirrors, and stained glass.27 Sculpture, which received particular attention during the Safavid period, is also incorporated into the palace’s ornamentation. Notable examples include the sculpted lions beneath the columns and the stone lions seated in the pool in front of the palace.28

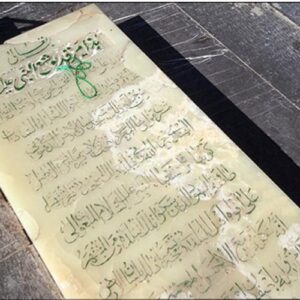

In addition to the inscriptions that indicate the dates of the building’s completion and restorations, two Quranic inscriptions have been installed in the shah-neshīn portico.29 The palace’s twenty wooden columns were once covered with mirrors and stained glass.30 The muqarnas-carved capitals, adorned with mirrors and stained glass, represent some of the earliest examples of this art form in Iran.31 The wooden sash windows (urusī), decorative lattice skylights, along with the inlaid and marquetry* doors, ceiling frames, and the inlaid pulpit of the palace, represent some of the finest examples of woodwork in this building.32

/Abdulkarim Attarzadeh/

Bibliography

Arbāb Eṣfahānī, Muhammad-Mahdi b. Muhammad-Reza. Neṣf-e Jahān fī Ta‛rīf al-Eṣfahān, ed. Manūchehr Sutūde. Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1961/1340.

Āzhand, Ya‛qūb. Maktab-e Negārgarī-ye Eṣfahān. Tehran: Vezārat-e Farhang va Ershād-e Eslāmī, Sāzmān-e Chāp va Enteshārāt, 2006/1385.

Behnām, ‛Īsā. “Hunar-e Naqqāshī dar Durān-e Pādeshāhī-ye Shah ‛Abbās-e Buzurg,” Hunar va Mardum, New Series, nos. 67–68, May–June 1968/Ordībehesht–Khurdād 1347.

Chardin, Jean, Voyages du chevalier Chardin en Perse et autres lieux de l’Orient, ed. L. Langlès, Paris : Le Normant, Imprimeur, 1811.

Dehmeshgī, Jalīl; Jānzāde, Ali. Jelveh-hā-ye Hunar dar Eṣfahān. [Tehran]: Jānzāde, 1987/1366.

Dieulafoy, Jean-Paul Rachel. Safar-nāme-ye Mādam Dieulafoy: Iran va Kalde, trans. and ed. Ali-Muhammad Farahvashī. Tehran: University of Tehran, 1982/1361.

Humāyī, Jalāl al-Dīn. Tārīkh-e Eṣfahān: Mujallad-e Hunar va Hunarmandān, ed. Māhdukht Bānū Humāyī. Tehran: Pazhūheshgāh-e ʿUlūm-e Ensānī va Mutāle‛āt-e Farhangī, 1996/1375.

Hunarfar, Luṭfullāh. “Kākh-e Chehel Sutūn.” Hunar va Mardum, no. 121, November 1972/Ābān 1351.

Hunarfar, Luṭfullāh. Āshenāʾī bā Shahr-e Tārīkhī-ye Eṣfahān. Isfahan: Gulhā, 1994/1373.

Hunarfar, Luṭfullāh. Rāhnamā-ye Abnīye-ye Tārīkhī-ye Eṣfahān. Isfahan: Chāpkhāneh-ye Emāmī, 1956/1335.

Jāberī Anṣārī, Muḥammad-Hasan. Tārīkh-e Eṣfahān va Rey va Hame-ye Jahān. Isfahan: Hussein ‛Emādzāde, [1943/1322].

Jāberī Anṣārī, Muḥammad-Hasan. Tārīkh-e Eṣfahān, ed. Jamshīd Maẓāherī. Isfahan: Mash‛al, 1999/1378.

Kaempfer, Engelbert. Safar-nāme-ye Kaempfer, trans. Keykāvus Jahāndārī. Tehran: Khwārazmī, 1981/1360.

Mehrpuyā, Jamshīd. “Munabbat va Kande-kārī-ye Chūb dar Me‛mārī-ye Iran-e Dure-ye Eslāmī,” in Tazʾīnāt-e Vābaste be Me‛mārī-ye Iran-e Dure-ye Eslāmī, ed. Muhammad-Yūsuf Kīyānī. Tehran: Sāzmān-e Mīrāth-e Farhangī-ye Keshvar, 1997/1376.

Musavī Fereydanī, Muhammad-Ali. Eṣfahān az Negahe Dīgar. Isfahan: Naqsh-e Khurshīd, 1999/1378.

Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, Karīm. Tārīkhche-ye Abīiye-ye Tārīkhī-ye Eṣfahān. Isfahan: Dād, 1956/1335.

Pāzūkī Ṭarūdī, Nāṣer; Shādmehr, ‛AbdulKarīm. Āthār-e Sabt-Shude-ye Iran dar Fehrest-e Āthār-e Mellī: az 24/6/1310 tā 24/6/1384. Tehran: Sāzmān-e Mīrāth-e Farhangī-ye Keshvar, 2005/1384.

Pope, Arthur Upham, A Survey of Persian art, Tehran: Soroush Press, 1977.

Robinson, B. W., “Painting in the post Safavid period”, in The Arts of Persia, ed. Ronald W. Ferrier, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Rustam al-Ḥukamā, Muhammad-Hāshem. Rustam al-Tavārīkh, ed. Muhammad Mushīrī, Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1969/1348.

Semsār, Muhammad-Hasan. “Āyīne-kārī dar Me‛mārī-ye Iran-e Dure-ye Eslāmī,” in Tazʾīnāt-e Vābaste be Me‛mārī-ye Iran-e Dure-ye Eslāmī, ed. Muhammad-Yūsuf Kīyānī, Tehran: Sāzmān-e Mīrāth-e Farhangī-ye Keshvar, 1997/1376.

Shafaqī, Sīrus. Jughrāfiyā-ye Eṣfahān, be ḍamīme-ye yekṣad va panjāh qeṭ‛e naqshe, nemūdār va ‛aks, 2nd ed. Isfahan: University of Isfahan Press, 2002/1381.

Sharīfzāde, ‛Abd al-Majīd. Dīvārnegārī dar Iran: Zand va Qājār dar Shīrāz. Tehran: Sāzmān-e Mīrāth-e Farhangī-ye Keshvar, 2002/1381.

Shāṭerī, Mītrā. “Chehel Sutūn,” in Dāʾerat al-Maʿāref-e Buzurg-e Eslāmī, vol. 19. Tehran: The Center for the Great Islamic Encyclopaedia, 2011/1390.

Vaḥīd Qazvīnī, Muhammad-Ṭāher b. Hussein. ‛Abbās-nāme, yā, Sharḥ-e Zendegānī-ye 22 Sāle-ye Shah ʿAbbās-e Thānī (1052–1073), ed. Ebrāhīm Dehqān. Arāk: Ketābfurūshī-ye Dāvūdī, 1950/1329.

- This article was previously printed in The Encyclopaedia of the World of Islam, vol. 12, pp. 221-224, and has been published in The Encyclopaedia Isfahanica with slight modifications.[↩]

- See: Jāberī Anṣārī, 1943/1322, p. 343; Hunarfar, 1956/1335, p. 70.[↩]

- Shāṭerī, p. 483.[↩]

- See: Hunarfar, 1972/1351, p. 3; ibid., 1956/1335, p. 67.[↩]

- See: Vaḥīd Qazvīnī, p. 91; Hunarfar, 1972/1351, pp. 6, 23–24.[↩]

- Hunarfar, 1956/1335, pp. 67, 70.[↩]

- Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, p. 53; Jāberī Anṣārī, 1943/1322, p. 344.[↩]

- Dieulafoy, p. 244; Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, p. 66.[↩]

- Arbāb Eṣfahānī, pp. 206, 245.[↩]

- Jāberī Anṣārī, ibid.; Mehrpuyā, p. 231; Semsār, p. 242.[↩]

- Dieulafoy, p. 245.[↩]

- Pāzūkī Ṭarūdī and Shādmehr, p. 69.[↩]

- See: Hunarfar, 1972/1351, p. 31; Shafaqī, p. 362.[↩]

- Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, p. 62.[↩]

- Kaempfer, vol. 1, p. 206; Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, p. 52; Chardin, vol. 7, p. 377.[↩]

- Arbāb Eṣfahānī, p. 34; Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, p. 53; Hunarfar, 1956/1335, p. 70, n.; ibid., 1994/1373, pp. 86–87.[↩]

- Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, pp. 54, 56–57, 59–60, 64.[↩]

- Jāberī Anṣārī, 1943/1322, p. 343.[↩]

- Jāberī Anṣārī, 1999/1378, p. 151; Shāṭerī, p. 485.[↩]

- See: Dahumeshgī and Jānzāde, p. 271.[↩]

- Hunarfar, 1956/1335, p. 70; Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, p. 64.[↩]

- Rustam al-Ḥukamā, p. 72; Kaempfer, p. 207.[↩]

- Rustam al-Ḥukamā, ibid.; Kaempfer, ibid.[↩]

- Hunarfar, 1994/1373, p. 87.[↩]

- Jāberī Anṣārī, 1943/1322, pp. 344–346; Hunarfar, 1972/1351, p. 12; Āzhand, pp. 276– 297; Sharīfzāde, pp. 107–109.[↩]

- Hunarfar, 1972/1351, p. 4; Humāyī, pp. 289, 320, 331–332; Behnām, p. 10; Robinson, p. 25.[↩]

- Chardin, vol. 7, p. 378.[↩]

- See: Pope, vol. 3, p. 1357.[↩]

- Hunarfar, 1972/1351, p. 25; Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, p. 59.[↩]

- See: Hunarfar, 1956/1335, p. 70; Chardin, vol. 7, p. 378.[↩]

- Musavī Fereydanī, p. 102; Pope, vol. 3, p. 1363.[↩]

- See: Nīkzād Amīrhuseynī, pp. 54, 57.[↩]