Kamarzarrīn, Mosque, one of the ancient mosques of Isfahan, located at the end of the Jūbāre* quarter.

According to documents from the Qajar period (r. 1795–1925/1210–1344), this mosque stood within the limits of the two neighborhoods of “Sayyed Aḥmadīyān” and “Kūche-ye Pā-shīr,” less than 150 meters east of the ‛Atīq congregational mosque*.1 This area originally belonged to or was adjacent to the village of Yahūdīyye*, and for this reason this part of the city should be associated with the pre-Islamic period. The foundation of the Kamarzarrīn Mosque most likely dates back to the Daylamid* era (r. 932–1055/320–447) or to the Seljuq* period (r. 1037–early 14th/429–early 8th century). Jāberī Anṣārī* (d. 1957/1376) also described this building as one of the “ancient mosques,” “near the Mīr square,” and belonging to the Daylamid period, though restored in later times.2 After him, Humāyī* (d. 1980/1359) considered the structure to be near the Mīr square and among the “very old mosques,” noting that it had been “repaired and renewed” during the Safavid* period.3 In his six-fold classification of Isfahan’s mosques, he placed this building, along with the Pīr-e pīnedūz* Mosque located north of the Kamarzarrīn Mosque, among the second-class mosques.4

The name of the mosque was recorded as “Kamarzarī” by Jāberī Anṣārī, Jenāb Eṣfahānī*, Humāyī, and Hunarfar* (d. 2006/1385); however, based on the description of Chardin*, the full name was “Kamarzarrīn,” which among the people was commonly pronounced as “Kamarzarī” with the elision of the final “n”.5 The earliest reference to the building is found in Chardin, who was in Iran in 1665/1075. In describing the Meydān-e Kuhne* and its surrounding space, he mentioned the ruins of the Qeyṣarīyye* or the old royal bazaar, and “beyond” it, three structures—a bathhouse, a caravanserai, and a mosque—all of which were called “Kamarzarrīn.”6 His account indicates that this quarter, at least in the Safavid period (r. 1501–1722/907–1135), contained spaces for commerce and the daily life of its inhabitants; but before that, and specifically until the Mongol invasion of Isfahan in 1255/633, this part of the city—once a Seljuq governmental center—must have had a different status, and research on this remains is ongoing. The western section of the mosque, extending towards the Meydān-e Kuhne, was demolished during the construction of the ‛Atīq [later Imam Ali] Square* underpass in the 1990s/1370s. In the mid-1970s/1350s, two German scholars, Heinz Gaube and Eugen Wirth, studied this area. They examined a raised mound, about 100 meters in diameter and 5 meters in height, which had been cut into during construction in 1973–1974, revealing cultural evidence. According to these two scholars, the mound represented the ruins of the Qeyṣarīyye or a palace on the edge of the square before the Safavid period, described as ruins by both Chardin and Kaempfer* in the second half of the 17th/11th century.7 It can thus be assumed that a significant structure once stood at the city’s center, which Gaube and Wirth dated to a time earlier than the construction of the Meydān-e Kuhne.8 Part of this site was destroyed under the project of “reviving the Seljuq square,” resulting in the loss of cultural evidence, but another portion still survives on the western side of the Kamarzarrīn Mosque. This has also been confirmed by archaeological geophysics studies, which revealed traces of a stone or brick structure—probably an arch or a paved floor—at a depth of about 5–6 meters below the current surface.9 Archaeological excavations in this area may help identify sections of the Kamarzarrīn Mosque, and the remains of the bathhouse and caravanserai mentioned by Chardin, and in the deeper layers, evidence from pre-Safavid periods down to the Seljuq era and earlier. In excavations conducted in 2023–2024 in the Kamarzarrīn passage, located north of the Kamarzarrīn Mosque, remains of the structure and movable artifacts were uncovered, dating from the early Islamic period through the Qajar and Pahlavi eras (r. 1925–1979/1304–1357). Among the most important finds were traces of the production and sale of metal, ceramic, and glass items. Moreover, a stone wall oriented northeast–southwest towards the congregational mosque was uncovered along the entire route. This wall, likely one of the city’s main thoroughfares and possibly dating to the formative period of Yahūdīyye or even earlier, once allowed access to the Kamarzarrīn Mosque until only a few decades ago, through what is now the new bazaar (Bāzār-e Ghāz).10

From 1991/1370, major alterations were made to the structure of the mosque, which damaged its authenticity. In the later inscriptions of the building, the dates 1416, 1425, and 1427, corresponding to 1995 and 2006, are recorded. Today, only through aerial photographs from earlier decades can the original structure of the mosque be partially discerned. According to Muhammad Ḥeydarī, the architect responsible for the mosque’s recent modifications, before the construction of the new northern prayer hall, there had been another prayer hall with a metal framework, probably dating to the 1970s/1350s, which appears in a photograph published in 1976/1355.11 Walter Mittelholzer, the Swiss aviator, took two aerial photographs of the congregational mosque and its surrounding fabric between 1923 and 1925/1302–1304, in one of which the Kamarzarrīn Mosque can be identified.12 The precinct of the Kamarzarrīn Mosque also appears in the aerial photograph of the congregational mosque taken by Erich Schmidt, the German-American archaeologist, in 1936, and in subsequent aerial surveys of Isfahan in 1956 and 1964, showing the structure in its earlier state.13 According to these documents, the southern vaulted hall of the mosque, the western prayer hall, and the courtyard remained—with some alterations—while the northern entrance and vaulted hall, the dome between them, and the eastern prayer hall were all demolished in later modifications, and additions were built over them. Further evidence for the existence of these earlier components, prior to their destruction, comes from the measurements recorded by Jāberī Anṣārī, who gave the dimensions of the mosque as more than “1.5 jarīb/acre,” [about 6070 square meter] and by Humāyī, who mentioned “1.5 acre” and elsewhere more precisely “44 dhera‛ by 40 dhera‛,” giving an area of “1760 square dhera‛.”14 Based on aerial photographs, if the mosque’s east–west length is taken as 40 dhera‛ (41.6 meters), the preserved east–west span of the old section amounts to only 24.8 meters. Similarly, if the north–south length is 44 dhera‛ (45.7 meters), the combined southern vaulted hall and courtyard extend 22.9 meters, showing that nearly half the surface of the old mosque was lost in the renovation programs. According to Ḥeydarī, the architect of the recent changes, after the 1990s the floor of the mosque’s western prayer hall was raised by about 80 centimeters, and a mill (bārvarzī) with an area of 240 square meters was added onto the new northern courtyard.

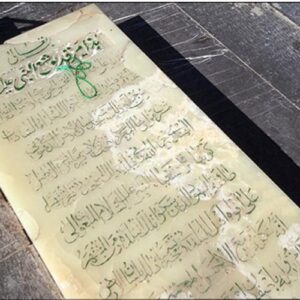

The western prayer hall, measuring 16.53 meters north–south and 8.8 meters east–west, once had a small doorway at its northern end, which is now blocked; instead, a new entrance has been opened to the south of the hall. The prayer niche (meḥrāb) of this prayer hall, decorated with ornamental ribbed vaulting (kārbandī) and painted ornamentation, is 2.15 meters high, 1-meter-wide, and 60 centimeters deep, and is set in the center of the southern wall. The border of the prayer niche was faced with tilework* in Mehr and Ābān 1337/October and November 1958/, bearing the text of Quran 2: 255–257 (known as āyatul-kursī), and at the end inscribed in nasta‛līq script: “The construction of the prayer hall of the Kamarzarrīn Mosque and its completion, through the assistance of the faithful and a number of devout and virtuous individuals, and through the efforts and diligence of Ḥāj Muhammad Nājī, the confectioner, was accomplished under the imamate of Ḥujjat al-Eslām Āqāy 9215 Ṭabībzāde, may his exalted shadow endure, in the month of Rabī‛ al-Thānī 1378/1958.”

The eastern side of the prayer hall opens onto the courtyard through three arches, each with piers 1.5 meters wide and 2.8 meters long; one of these has been completely rebuilt. In the southern section, another entrance, measuring 1.4 meters (north–south) by 0.8 meters wide, connects the hall to the southern vaulted hall, which has likewise been reconstructed with facing brick. The southern vaulted hall is 15.26 meters long (east–west) and 5.2 meters wide (north–south), and it is distinguished from the prayer hall by three bays. The bays measure 3 meters wide (north–south), with the side entrances each 3.44 meters and the central bay entrance 5.05 meters (east–west), which leads to a new tiled meḥrāb (added after the 1990s/1370s). At the center of the prayer hall is a brick dome 6.15 meters high, decorated in mosaic tile* with the word “Allah” and the names of the Five Members of the Prophet’s Household inscribed at its apex. The courtyard of the mosque (14.7 by 14.7 meters) is now roofed, though it once contained a pool in its northern part that was removed in recent renovations. This pool, measuring about 2 by 4 meters, appears in the aerial photograph of 1956/1335, and is still remembered by the older residents of the neighborhood. The only surviving decoration of the courtyard is geometric inlaid tilework (ma‛qelī tilework( with the words “Allah,” “Muhammad,” and “Ali,” executed on the western wall of the courtyard and at the entrance to the prayer hall.

On the eastern side, a new prayer hall known as the Ḥemmaṣī Hall has been built. Its inscription dates to 1991/1370, during the imamate of Muhammad-Ali Nāṣerī*. This section replaced the mosque’s old prayer hall, which according to elderly residents had once contained a doorway on its southern side leading to the Bāzār-e Ghāz. In this way, besides the main northern entrance, the mosque—following one of the common patterns of mosque architecture—had two additional entrances on the east and west. Part of the northern section of the new prayer hall formerly contained the endowed public water-dispensing structure adjacent to the Kamarzarrīn Mosque, which now functions as an ablution facility. The water-dispensing was endowed on 27th November 1698/23 Jumāde al-Awwal 1110, and its endowment document is preserved both in a manuscript copy and in a registered transcript from 1930/1309.16 In this later document, a man named ‛Abdul-Rasūl Ḥājī-Mīrzāʾī is mentioned as the custodian (mutawallī), showing that this water-dispensing —still faintly remembered by elders as the “Ḥājī-Mīrzāʾī”—is indeed the same structure adjacent to the Kamarzarrīn Mosque, and its location can be identified. Identifying the location of this building and the adjoining shops in the endowment document provides important information about the neighborhood known as “Pā-shīr” at the head of the bazaar and about its urban structure. In a set of correspondences from 1940/1319 regarding the deterioration of the water-dispensing, both the names “Ḥemmaṣī” and “Ḥājī-Mīrzāʾī” are used for the structure, showing that it was the same place known under two different names.17 The endowment document also designated a chamber for the burial of the founder within the water-dispensing. During the modern reconstruction, the gravestone of the founder, dated 1710/1121, together with the gravestone of his son, Ḥājī Bāqer, his successor as custodian, dated 1715/1127, were mounted on the wall of the water-dispensing.

Among the congregational imams of the mosque in the contemporary period were: Muhammad Ṭabībzāda* (d. 1970); Ḥasan Ṣāfī Eṣfahānī* (d. 1995), buried in the mausoleum of ‛Allāma Majlesī*; and Muhammad-Ali Nāṣerī (d. 2022), buried in the Tekīye-ye Shuhadā of Takht-e Fulād*. Nāṣerī assumed the imamate of the Kamarzarrīn Mosque in 1980/1359 upon the recommendation of Ṣāfī Eṣfahānī. His public lectures at this mosque became widely renowned and popular because of their ethical and apocalyptic themes.18

/Ali Shojaee Esfahani/

Bibliography

asnād-e mawqufāt-e Isfahan, scientific supervisor: Ṣādeq Ḥusaynī Eshkevrī, Qum: Majma‛-e Dhakhā’er-e Eslāmī, 2009/1388.

Chardin, Jean, safarname-ye Chardin, trans. Eqbāl Yaḡmāʾī, Tehran: Ṭūs, 1993–1996/1372–1375.

Chardin, Jean, Voyages du chevalier Chardin en Perse et autres lieux de l’Orient, ed. L. Langlès, Paris: Le Normant, Imprimeur-Libraire, 1811.

Gaube, Heinz, and Wirth, Eugen, Der Bazar von Isfahan, Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert, 1978.

Getarchive, 2025.Retrieved Sept.17,2025, from https://itoldya420.getarchive.net/amp/media/

Humāyī, Jalāl-al-Dīn, ketāb-e tārīkh-e Isfahan: mujalled-e abnīye va ‛emārāt va āthār-e bāstānī, ed. Māhdukht Bānū Humāyī, Tehran: Humā, 2005/1384.

Humāyī, Jalāl-al-Dīn, tārīkh-e Isfahan: mujalled-e jughrāfiyā-ye Eṣfahān, ed. Māhdukht Bānū Humāyī, Tehran: Pazhūheshgāh-e ‛Ulūm-e Ensānī va Muṭāle‛āt-e Farhangī, 2019/1398.

Hunarfar, Luṭfullāh, ganjīna-ye āthār-e tārīkhī-ye Eṣfahān, Isfahan: Saqafī, 1965/1344.

Isfahan, city of light: an exhibition organized by the Ministry of Culture and Arts of Iran in association with the World of Islam Festival by Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, Tehran: Ministry of Culture and Arts of Iran, 1976.

Jāberī Anṣārī, Muhammad-Ḥasan, tārīkh-e Isfahan, ed. Jamshīd Maẓāherī, Isfahan: Mash‛al, 1999/1378.

Jenāb Eṣfahānī, Ali, al-Eṣfahān, ed. Muhammad-Reza Rīāyḍī, Tehran: Sāzmān-e Mīrāth-e Farhangī-ye Keshvar, 1997/1376.

Khabarguzārī-ye Shabestān, 2022/1401.

Retrieved Sept. 15, 2025, from https://www.shabestan.news/news/1209327.

“Mawqūfe-ye saqqākhāne-ye Ḥāj-Mīrzāʾī dar Eṣfahān,” Sāzmān-e Asnād va Ketākhāne-ye Mellī, no. 15375/250.

Retrieved Sept.17,2025, from https://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/search/briefListSearch.do?

Schmidt, Erich Friedrich, Flights over ancient cities of Iran, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, [1940].

Shojaee Esfahani, Ali, “guzāresh-e muqaddamātī-ye ‛amalīyyāt-e meydānī-ye kāvesh-e bāstānshenāsī-ye shahrī-ye eḍṭerārī dar guzar-e Kamarzarrīn, mujāver-e Masjed-e Jāme‛-e shahr-e Eṣfahān,” Isfahan 2023–2024/1402–1403 (unpublished).

Sulṭān Sayyed Reza Khān, naqshe-ye dār al-salṭana-ye Isfahan, scale 1:4000, Isfahan: Maṭba‛ea-ye Mīrzā Hussein Farhang, 1923/1302.

Uveysī-Muqaddam, Muḥsen, “guzāresh-e muṭāle‛āt-e archaeological geophysics dar maḥdūde-ye Meydān-e Kuhne-ye Eṣfahān, guzar-e Kamarzarrīn,” Isfahan 2025/1404 (unpublished).

- Jenāb Eṣfahānī, p. 72; asnād-e mawqūfāt-e Isfahan, vol. 1, pp. 277–299, vol. 8, pp. 29–48; Sulṭān Sayyed Reza Khān, 1923/1302[↩]

- Jāberī Anṣārī, p. 124.[↩]

- Humāyī, 2005/1384, pp. 220, 239.[↩]

- Ibid., p. 220.[↩]

- Jāberī Anṣārī, p. 124; Jenāb Eṣfahānī, p. 72; Hunarfar, p. 856.[↩]

- Chardin, vol. 7, pp. 480–481; Chardin, safarname-ye Chardin, trans. Persian, vol. 4, pp. 1503–1504.[↩]

- Gaube and Wirth, pp. 32–33.[↩]

- Ibid., p. 8.[↩]

- Uveysī-Muqaddam, 2025/1404.[↩]

- Shojaie Isfahani, 2023–2024/1402–1403.[↩]

- Isfahan, city of light, p. 21.[↩]

- Getarchive, 2025.[↩]

- Schmidt, pl.27.[↩]

- Jāberī Anṣārī, p. 124; Humāyī, 2005/1384, pp. 220, 239; Idem, 2019/1398, p. 283.[↩]

- This number corresponds, based on Abjad numerals, to “Muhammad” in the inscription of the calligrapher. Abjad numerals is a system to calculate numbers by assigning the specific values to the specific letters of the Arabic alphabet.[↩]

- asnād-e mawqūfāt-e Isfahan, vol. 1, pp. 277–299, vol. 8, pp. 29–48.[↩]

- “Mawqūfe-ye saqqākhāne-ye Ḥāj-Mīrzāʾī dar Eṣfahān.”[↩]

- Khabarguzārī-ye Shabestān, 2022/1401.[↩]